This week, I want to talk you through a job that I used to do. First, a bit of explanation, don’t worry, I’ll try not to get too technical and boring. At the end of the post, there’s a video of me at work.

I used to be a ship’s pilot, working on the River Thames. I was employed by the Port of London to be an expert on the river, to know all its depths and currents, the positions of the berths and the safest way to arrive and depart from any of them. I was authorised to pilot ships of any size (up to the maximum that was physically possible), anywhere in the estuary and river as far upstream as London Bridge, which is one further than Tower Bridge.

I used to go to work never knowing what ship I would be boarding, or where I would be going. It made for an interesting life, I liked to compare it to driving down a road, except that the road was moving. Even in the same place, the flow of the river changed dependant on the state of the tide, the depth of water and the resultant contours of the river bed.

As well as the ships we had never seen before and had to get used to handling very quickly, there were regular customers, one of which arrived every Tuesday and Saturday.

The ships on this service were 171 metres long, there were three of them, all the same design and they went into Tilbury lock.

We would board by rope ladder at Gravesend for the last bit, taking them around Tilburyness and turning them to enter the lock. At Tilbury, as at all the berths on the river, we used the flood tide as an aid to turn the ship. Knowing where it was strongest and where it was weakest was all part of the job, especially on lower-powered ships with limited manoeuvrability or room. At Tilbury, the strongest tide was on the opposite side of the river to the lock, it could be used to push the vessels stern around as the bow came into the weaker flow of water behind the corner. The trick was to get the ship into the right position to extract the maximum assistance. If you timed it right, as the tide pushed you could move ahead out of the current when you were lined up for the lock.

After a few years, you could usually make it look easy. Of course, when the wind was howling it took a bit more concentration, so there was less time to take pictures. And the further upriver you went, the less room you had.

Once you pass through the Thames Barrier, more so above Greenwich, the river starts to resemble a muddy ditch, whilst places like Barking Creek are little more than streams. Any vessel over 100 metres in length bound above Tower Bridge has to be reversed either inwards or outwards as there is no room to turn it off H.M.S. Belfast or just below London Bridge. The paddle Steamer Waverly, for example, can only be turned above Tower Bridge if it has the assistance of a tug.

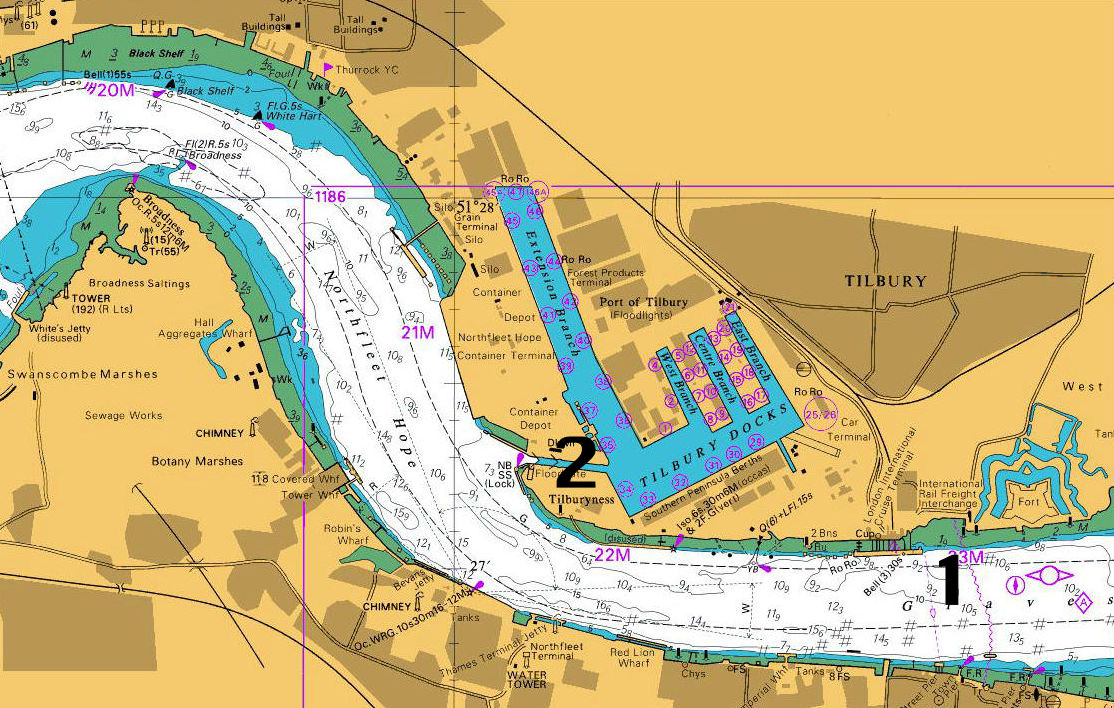

So, going back to our ship bound for Tilbury lock. If you look at this map, we start at position 1, heading left for position 2.

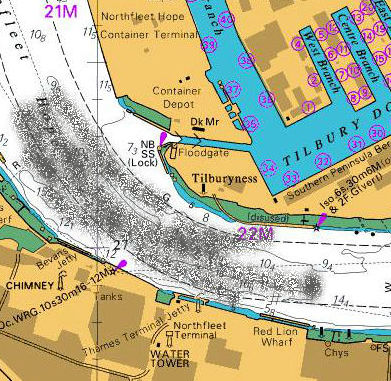

The river is flowing from right to left as we look. Here’s the view from the ship at position 1.

Looking at this picture,

the current pushes from right to left around the corner, strongest where the shading is. Above the shading, the water is almost still.

Hence if you position the ship properly, the river does all the work, you just control the effect. As you can see in these pictures.

Finally, we are out of the current and heading into the lock, we have about 3 metres on each side.

Another job successfully completed.

If you’re interested, here is an excerpt from National Geographic “Megacities” made a while ago, featuring a much younger me, taking a sailing ship through Tower Bridge.

Next week, I’ll be posting a book review from a blog tour that I’ve been involved in.

![]()